The following article is an extract from The Travel Magazine, published in 1905. The article is written by R. N. Rudmore Brown, possibly a naturalist at the turn of the century and certainly a lecturer at Sheffield University. Rudmore Brown divulges his observations of daily life and how he sees the Moken and local people in the Mergui Archipelago at the beginning of the 20th Century. This article provides a fascinating tool for comparison when we visit the area now in the early 21st Century.

The Mergui Archipelago

There is probably no part of the lands bordering the Bay of Bengal which today is so seldom visited and remains so little explored as extreme lower Burma and the Mergui Archipelago. Lower Tenasserim lies apart from the travel routes of the East, while its own productions are too small to bring into prominence.

It fell to my lot to spend some months in this district while investigating, with my friend and colleague, Mr. James J. Simpson, the pear fisheries of the Mergui Archipelago on behalf of the government of India. In attempting to give some insight into this archipelago and its remarkable inhabitants I can choose no more suitable starting point than the town of Mergui the “big town” of the coast and the capital of the archipelago on one of those islands it stands.

It fell to my lot to spend some months in this district while investigating, with my friend and colleague, Mr. James J. Simpson, the pear fisheries of the Mergui Archipelago on behalf of the government of India. In attempting to give some insight into this archipelago and its remarkable inhabitants I can choose no more suitable starting point than the town of Mergui the “big town” of the coast and the capital of the archipelago on one of those islands it stands.

Nestling between river and jungle Mergui is half hidden until one comes abreast of it. Unless one arrives on Friday, the mail-boat day, the town seems peacefully asleep in the heavy scent-laden air, and one wonders why so drowsy and quiet a community continues to exist. A mile or more along the shore stretch the brown palm-thatched houses, among which rise palms and flowering trees, while beyond this is a background of towering jungle.

However Mergui is not the sleepy place that it looks from the sea; there is plenty of life and stir in its streets and market places.

Its bazaar is alive with a glowing panorama of half the races of the east – China man and Burman jostle one another; Madras coolies, Malays and Siamese are all to be seen, each in his native dress; while among them move Japanese and Filipinos, both in white ducks, and former especially haughty with their self assured superiority, a few wild looking Selungs clad in the scantiest of raiment, from the islands beyond and last and least frequent the European.

Each element of this cosmopolitan crowd seems in its own way seems to be busy, for Mergui is a thriving town which is growing year by year. And it does not take the stranger long to find out that the source of his prosperity is the archipelago and principally its pearl shell fishing, with which of course is allied in minor capacities the trade in bech de mer, Turtle shell, edible birds nest and other products of the island waters.

During the pearling season the talk and gossip are all of the Mergui Archipelago, of this or that pearl, of a certain divers luck or of another’s exploits.

It is the same wherever there are pearl fisheries: the risk and uncertainty, the strong element of chance which makes a stroke of fabulous luck quite possible any day, have an irresistible appeal and one whose infection is very contagious.

Leaving Mergui by a narrow channel between the jungle clad shores of two large islands and past half a dozen quaint little fishing villages we reach the waters of the Mergui Archipelago. For near three hundred miles this island studded sea extends from North of Tavoy Point southward to beyond the Anglo Siamese frontier an area little short of ten thousand square miles. Among the two hundred islands are umbered those of every size, from mere islets, little more than rocks, to a few of five, ten or even twenty miles in length, and of every outline from flat sandy cays to hills of several hundred feet. But practically all are covered with dense jungle interwoven with lianas into an almost impenetrable mass.

Very generally the islands meet the sea in steeply sloping rocks or in vertical cliffs, but every here and there is beautiful shelving beach glittering in the sunshine save where the tall jungle trees cast their shadow; places of idyllic charm in themselves, and doubly so in contrast to the noisome evil smelling mangrove swamps that normally fringe the mainland. As a rule tropical scenery, more especially on the coasts, is monotonous and often unbeautiful, but here is no sameness;

Very generally the islands meet the sea in steeply sloping rocks or in vertical cliffs, but every here and there is beautiful shelving beach glittering in the sunshine save where the tall jungle trees cast their shadow; places of idyllic charm in themselves, and doubly so in contrast to the noisome evil smelling mangrove swamps that normally fringe the mainland. As a rule tropical scenery, more especially on the coasts, is monotonous and often unbeautiful, but here is no sameness;

the diversified scenery has always some new charm or unlooked-for wonder for the traveller.

Yet wildlife is scarce but for the troops of monkeys the harsh crying horn-bills and the pigeons. It is not surprising to find most of the islands uninhabited, but there are nevertheless several exceptions, apart from the nomadic fishermen of whom I shall speak later. On Tavoy Island is a large community of Christianised Karens, with a native schoolmaster in there midst. One Sunday when I visited them they held a service in a jungle glade that served for a church, and most charming did the congregation of maidens look – for no men attended all gaily dressed in coloured silk, their black hair decked with orchids.

Many of the islands near the mainland have temporary settlements of Burmese fishermen during the fine season, but during the rains all these are abandoned. Built on stakes above the mud banks these villages are very picturesque externally, but not so nearly so desirable when one enters them. The only means of access is a rickety vertical ladder, the foot of which one reaches by boat. At the top is a frail platform of bamboos, on which numerous huts are built: at low water the foul smell of the mud pervades the atmosphere, and the eerie sound of the crackling mangrove oysters is ever present, while a false step or too heavy tread would precipitate one to the mud twenty feet below. The fish are caught in large traps formed converging lines of stakes, which is common form in Eastern waters.

Among various other stragglers in the Mergui Archipelago I must make mention of certain Malay fishermen in the south whom the natives insist, and I think with some reason, are more pirates than anything else. In bygone days sailing ships dreaded to be becalmed near these pirate infested islands; but while the day of large scale robbery is past, in these seas at least,there is plenty of scope for piracy of a meaner sort against the pearling boats and Chinese junks which frequent the archipelago. When I visited that region our Burmese diver and his coolies were only reassured by the presence of a government launch, and I think they were glad to leave for more northern waters when our work was done. Nor is that an isolated case of fear on the part of the pearl divers.

The Moken

Of all the people to be found among the Islands of the Mergui Archipelago, the most interesting are that strange race of nomadic fishermen known as the Selungs (Moken), or Moken Sea Gypsies, a people who seldom stray beyond their home in the Mergui Archipelago, unless a few of the boldest make a visit to Mergui.

In cruising through the island group it is not uncommon to catch sight of one or two tiny square sailed boats hurrying along, or, in rounding the point of an island to find a small encampment on a sandy beach.

A more timid people can scarcely be found. They live in dread of strangers of any kind, and a steam launch with white men seemed to suggest to them merely pirates of another color from the Malay dacoits at whose hands they have frequently suffered. As we approached such a beach encampment there was a general stampede, and before we landed there was often not a single human being on the beach, even the dogs turned tail with their masters and vanished into the jungle. On several occasions I found such deserted encampments with boats drawn up on the beach, fires burning, and a meal cooking, but no sign of occupants. I entered the jungle with an interpreter in search, but no trace of them was to be found, though no sooner had we put to sea again than those elusive people once more flocked down to the beach.

On a few occasions, however, I contrived it might have to be by cajolery or craft to get at close quarters with the Moken and to hold converse through an interpreter. Even that was difficult, for they have a language of their own in which my interpreter was not well versed, and it is only a

On a few occasions, however, I contrived it might have to be by cajolery or craft to get at close quarters with the Moken and to hold converse through an interpreter. Even that was difficult, for they have a language of their own in which my interpreter was not well versed, and it is only a

few among them who trade with Mergui, or with the rascally Chinese merchants who visit them, that speak Burmese.

The children are pitiably timid. I have seen them jump overboard and swim for the shore or break into violent fits of sobbing when we ran alongside the boats. But they listened in amazement to the screech of our launch’s steam whistle, and when they saw the propeller revolve neither old nor young could suppress their delight. Despite their savage, gaunt and even forbidding appearance, the Moken are invariable peaceful and unaggressive.

Throughout the fine season the Selungs (Moken) wander through the Mergui Archipelago in their frail boats, which form their real homes. These boats, about twenty feet long, have a solid dug out for hull, with upper-works of palm leaf strips lashed to uprights and made watertight with a coating of dammer. A few seats, a palm leaf awning, and a sail of plaited palm leaf complete the boat. No metal is used in the construction, and the only tool employed is a rough adze; in fact beyond their fishing spears and these adzes the Moken possess no weapons or tools of any sort.

Nor is their household property extensive, for to such confined nomads property would be a serious hindrance to free movement.

A few earthenware cooking pots, two or three bamboo water carriers, some broken crockery (usually made in Germany) and a couple of empty kerosene tins (and where are they not to be found?) complete the list. Clothes do not trouble the Moken; a scanty loin cloth suffices for both sexes though the younger women wear more when they can get it, and some of the men have adopted the Burmese Lungi. The only objects they lay great value on are their trident shaped fishing spears, the iron for which if not the fashioned spear, they get by barter from the mainland.

The Moken occupy themselves almost entirely in fishing, or in diving for various kinds of mother of pearl shell, but occasionally they scour the jungle in search of honey, or hunt wild pigs with the aid of their dogs. There are places among the islands where they have planted plantains, mangoes and pineapples, but they pay little attention to these “Gardens” only visiting them on rare intervals. All their energy seems to be absorbed in obtaining the days scanty living, consisting of fish, oysters, honey, and fruit, with the occasional pig or turtle. I seldom saw in their boats sufficient food for more than the next meal.

The Moken occupy themselves almost entirely in fishing, or in diving for various kinds of mother of pearl shell, but occasionally they scour the jungle in search of honey, or hunt wild pigs with the aid of their dogs. There are places among the islands where they have planted plantains, mangoes and pineapples, but they pay little attention to these “Gardens” only visiting them on rare intervals. All their energy seems to be absorbed in obtaining the days scanty living, consisting of fish, oysters, honey, and fruit, with the occasional pig or turtle. I seldom saw in their boats sufficient food for more than the next meal.

During the fine season they pass from island to island in the Mergui Archipelago, never staying more than a night or two in the same place, but when the stormy weather of the south west monsoon sets in and the fishing operations have perforce to be abandoned, the Moken betake themselves to sheltered inlets, where they build rude cheerless dwellings in which they pass the months of waiting until the propitious weather comes again. During these summer months of enforced sedentary life they repair their boats, and weave a few palm leafed mats for use and for sale, all the while, no doubt, dreaming of their liberation when the storms are over. A miserable life it is true, and yet these sea gypsies seem to be a happy people, and to show no signs of dying out. There must be some 900, I estimated in the archipelago. With the exception of a few at Junkseylon, on the mainland of the Malay peninsula, their range is limited to the islands.

Cantor Island & Pearl Fishing

Before leaving these strange people I must mention one rather anomalous tribe I visited who seem to have overcome very largely their nomadic propensities, and have formed a permanent settlement on Cantor Island, not far from Mergui. The settlement is not extensive. A square mile or so – the whole island has been cleared of jungle, and about a dozen families have built moderately substantial huts on the sheltered side.

Before leaving these strange people I must mention one rather anomalous tribe I visited who seem to have overcome very largely their nomadic propensities, and have formed a permanent settlement on Cantor Island, not far from Mergui. The settlement is not extensive. A square mile or so – the whole island has been cleared of jungle, and about a dozen families have built moderately substantial huts on the sheltered side.

Here I had the pleasure of being presented to the chief, who was very communicative on the subject of his tribe and the Mergui Archipelago in general.

Plantains, Pineapples, and cotton trees are cultivated, while, of course, fishing is carried on. A certain amount of barter takes place with Mergui, or the Chinese merchants from whom the Moken buy rice at exorbitant prices in exchange for cotton pods, fruit and pearl shell. The Cantor Island community, the only one I believe with a chief, have progressed considerably over their purely nomadic Moken brethren. They have a sufficiency of food, a surplus of produce for barter, and they are less suspicious of strangers than the rest of the race.

Tropical islands and their sheltered waters yield a number of economic products, such as bech de mer, turtle eggs, tortoise shell, edible birds nests, and pearl shell. The Mergui Archipelago has a trade in all these, but the only one I can speak of here is the pearl and mother of pearl shell industry. The shell fished is the giant mother of pearl oyster, and the conditions of the industry are rather exceptional, in as much as the shell is now only to be found in deep water, which not only precludes all naked diving, but demands divers of more than ordinary skill and endurance. The Mergui divers, who are all Japanese, Malays, Filipinos, or rarely Burmese and Chinese, commonly descend to twenty eight or twenty nine fathoms, while one or two Japanese told me they could go even a fathom deeper, but this is very dangerous, and often results in paralysis.

Of course a diver who can descend even a few feet lower than the rest is in great demand among the pump owners. He can practically dictate his terms and get anything in reason, and even a little more. When a twenty nine fathom man happens to be a Jap his swagger and arrogant offensiveness would be hard to beat, but

divers of other nationalities, except when under the influence of their favourite brandy, are pleasant and friendly men.

They almost all speak English, sometimes more viral than fluent and ashore wear European dress, which is not considered complete without a black coral walking stick. When at work they demand for themselves and their tenders what they are pleased to call European rations which consist of fresh meat, tinned foods, especially sardines, and invariably a bottle or two of brandy. The life is undoubtedly risky, but the pay is good and enables the diver during the wet season to live in idleness and luxury. A first class man, moreover, is often paid a retaining fee during the “off” season.

They almost all speak English, sometimes more viral than fluent and ashore wear European dress, which is not considered complete without a black coral walking stick. When at work they demand for themselves and their tenders what they are pleased to call European rations which consist of fresh meat, tinned foods, especially sardines, and invariably a bottle or two of brandy. The life is undoubtedly risky, but the pay is good and enables the diver during the wet season to live in idleness and luxury. A first class man, moreover, is often paid a retaining fee during the “off” season.

The pearling fleet consists of some eighty small schooners, which work on various banks throughout the Mergui Archipelago, returning every alternate spring tide season when diving is impossible, to refit at Mergui. On board each boat the owner has a representative who opens the shells and collects the pearls, when they occur. This is an exciting moment. As often as not there may be no pearls, or none of any great value, but every now and then a large one of rare luster and perfect shape is found. Often, however, the pearls do not occur free in the oyster, but are contained in “blisters” on the mother of pearl. Now, since these

blisters do not invariably contain pearls, there is a unique oppotunity for a little gambling.

The blister is often offered for sale unopened, and a dealer will buy it on the chance of its containing a valuable pearl.

Just before I came to Mergui three “sportsmen” had formed a syndicate to buy a large unopened blister, which they acquired for a relatively small sum. On opening it they found two pearls whose total value was over 3,300 pounds. This I think constitutes a record for Mergui, but gems worth 100 or 200 pounds are not seldom found. Considering the small number of days in the year only about seventy on which work is possible on account of tides and weather, I think one may look upon the Mergui Archipelago pearl fisheries as fairly remunerative to all concerned. They are not pefacrhaps what they once were, but there is no reason why, with careful application of scientific knowledge and a little outlay, they should not give increased returns in the future.

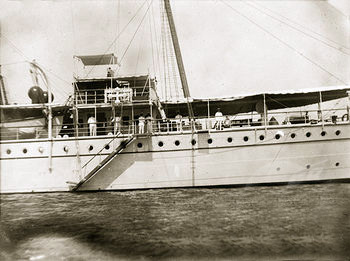

In leaving the Mergui Archipelago I must say a word about the R.I.M.S Investigator (Commander W.G Beauchamp R.I.M), the ship in which most of my journeys through the island waters were made. No one whose work whose has lain in Indian lands but has heard her name, while in a world of science she is famous. For over twenty seven years the Investigator has pursued her work of surveying, sounding, and deep sea dredging in Indian waters from Aden and the Persian Gulf to Mergui, until, I may safely say, most of our knowledge of Indian waters is due to her. This voyage in the Mergui Archipelago was her last service, for the old Investigator’s day is over, and the ship breaking yard will shortly claim her, while a new, better equipped, faster and, be it said, more seaworthy Investigator continues the work. Yet it will be long before the fine new ship, the third of her name, becomes as familiar in Indian ports, as integral a

In leaving the Mergui Archipelago I must say a word about the R.I.M.S Investigator (Commander W.G Beauchamp R.I.M), the ship in which most of my journeys through the island waters were made. No one whose work whose has lain in Indian lands but has heard her name, while in a world of science she is famous. For over twenty seven years the Investigator has pursued her work of surveying, sounding, and deep sea dredging in Indian waters from Aden and the Persian Gulf to Mergui, until, I may safely say, most of our knowledge of Indian waters is due to her. This voyage in the Mergui Archipelago was her last service, for the old Investigator’s day is over, and the ship breaking yard will shortly claim her, while a new, better equipped, faster and, be it said, more seaworthy Investigator continues the work. Yet it will be long before the fine new ship, the third of her name, becomes as familiar in Indian ports, as integral a

part of Indian seas, her predecessor, the picturesque and leisurely wooden paddleboat.

The Mergui Archipelago

By R.N. Rudmore Brown

Lecturer in Geography, Sheffield University

1905 article from Travel Magazine.